Return to NORTHCOM

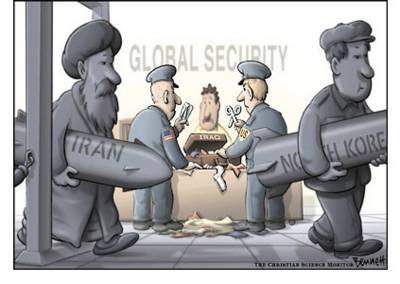

The Power to Crush, Even to Threaten to Crush, is an Arrow That has Been Removed from the Imperial Quiver.

August 26 , 2004

By Tom Engelhardt

Last week, Jonathan Schell and I exchanged letters on the nature of the American empire, based in part on his analysis, in his book The Unconquerable World, of three centuries of armed as well as unarmed resistance to various imperial urges by the peoples of our planet. Now, he has taken up the subject of imperial America again in his latest "Letter from Ground Zero" in this week's issue of the Nation, which the editors of that magazine are kindly letting me post at Tomdispatch.com. What follows is an adapted version of my response to that letter.

Return to NORTHCOM

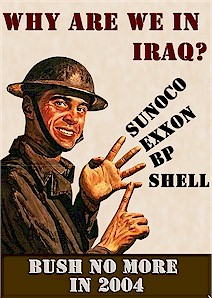

The slew of letters our previous exchange about empire brought into the Tomdispatch e-box indicates that we're hardly the only ones with empire on the brain. Letter-writers, articulate and thoughtful, young and old, wanted to remind us that the U.S. had always been an empire; or that the real imperial thrust of the globe was corporate and/or consumerist (that, for instance, whatever happened to the Bush administration, KBR, the base-building, military-supporting wing of Halliburton, was already victorious); or that the Cold War itself may have been little but a cover for ongoing imperial politics ("Did the Cold War exist objectively, or was it a name for U.S. colonial foreign policy? Will the Cold War come to be seen as a minor episode in the multi-century history of colonialism?"), or a score of other things, almost all provocative, all reminding us that beyond the blathering, confusing torrent that is now our media, critical thought is still alive among our citizenry.

It seems perhaps less alive in Iraq where our imperial centurions have been pounding the daylights out of Najaf, Falluja, and other Iraqi cities. Here, for instance, is a description from Luke Harding, a British Guardian correspondent, of an intense bombardment in downtown Najaf as seen from the roof of his hotel, just over a mile from the Shrine of Imam Ali: "It's really, really relentless -- there's a war plane circling above me, and straight ahead beyond the palm trees there are puffs of black smoke from the Old City, which has been repeatedly hit and pulverized… To my right, over in Najaf's old cemetery, two Apache helicopters have been circling and re-circling all afternoon, I think just picking off Mahdi army fighters among the graves."

Alex Berenson and Sabrina Tavernise of the New York Times recently quoted Lt. Col. Myles Miyamasu, commander of the First Battalion of the Fifth Cavalry in Najaf as saying ("Overwhelming Militiamen, Troops Push Closer to Shrine," Aug. 24), "We want to destroy the enemy, destroy his will, make him fight on our terms. Slowly but surely, we're achieving that." It's the sort of military statement that you could have found in any old history book of colonialism (or that could have come straight from America's Vietnam experience).

At the end of a startling three weeks of fierce resistance to the world's most powerfully armed military in Najaf, Baghdad's Sadr City, and elsewhere in southern Iraq by lightly armed, largely untrained, poor, unemployed Iraqi men and boys, perhaps the Shrine of Imam Ali will indeed fall to the Marines -- or to the battalion of recently trained but clearly reluctant Iraqi troops the Americans are threatening to shove into the breach so that infidels will not actually occupy the holy ground. (Do we believe that no one sees through this sort of transparent maneuver -- transparent at least anywhere other than in the United States?)

But should it really be so hard for Americans, who from the Alamo and the Little Big Horn to Pearl Harbor have such a tradition of mobilizing "last stands," of, in short, mythologized acts of national martyrdom, to grasp that such a (delayed) "victory" by the world's last superpower with its Apache helicopters, F-16s, and Predator drones, against desperate locals (local to Iraq, if not Najaf itself) can't be a victory for long, though -- to be thoroughly cynical -- perhaps it's only meant to be long-lasting enough for next week's Republican convention. Or perhaps the aging Grand Ayatollah Ali Sistani will indeed ride to everyone's rescue.

On this I'm convinced, though -- whatever may once have been the case, the world is, as you argue, now ungovernable by these older imperial methods and the military-style thinking that goes with them (though whether there's a more effective, newer style of imperial governance, as so many readers suggested, that passes under the misnomer of "globalization" is another question entirely). In fact, I'm convinced that, from the global (nuclear) realm to the local (popular resistance) realm, the power to crush, even to threaten to crush, is an arrow that has somehow been removed from the imperial quiver (though the power to destroy grows ever greater).

Perhaps this was the true message that, during all those Cold War years, lay embedded in the superpower nuclear standoff that went by the all-too-appropriate initials of MAD (mutually assured destruction), and that remains no less operative in the supposedly "unipolar" world that has followed. In other words, as you've also argued, at both the Brobdingnagian and the Lilliputian levels -- at both the imperial head and the imperial feet -- a kind of ruling paralysis has set in for the last standing empire. There is, of course, irony in this, because if the Bush administration was intent on demonstrating anything, it was that the restraints once so much the essence of the Cold War superpower standoff had long ago fallen away and that the United States was capable of pursuing a path of global domination of its choosing without fear of contradiction, significant opposition, or possible defeat. It has, with remarkable success, demonstrated the opposite. As we see in the smashed Old City of Najaf, a power to destroy remains, but what seems beyond its grasp is ruling even a single other country in the style once so familiar to students of the British, French, Japanese, or German empires.

This is the imperial roadblock they've come up against in Iraq and elsewhere abroad, and both of us in our letters have been looking abroad -- to that terrain, that landscape, for which empires are supposedly made. But what if we look instead to our "homeland" -- an ominous term only recently introduced here that seems swiftly to have replaced "country" or "nation" and that, with its Germanic overtones, hints at where we've been headed these last years. Whatever our military can't do abroad (despite its staggering technological power), it has proved capable indeed of quite peacefully transforming our society at home, which in the last sixty years has experienced a striking, if until recently hardly noticed, degree of militarization.

The militarization of the United States, which started during World War II, accelerated in the 1950s with the creation of a "national security state" and Eisenhower's famed "military-industrial complex" (with its "revolving door" for employment between its military and industrial halves, and the artful scattering of military bases in congressional districts nationwide, not to speak of the artful seeding of funds and plants for the production of new weaponry hardly less widely). Washington in those years became a war capital and was rapidly Pentagonized. After a post-Vietnam dip, militarization proceeded apace in the Reagan years with the Pentagon functioning ever more as a central ministry for basic and advanced scientific and technological research and development (in a country that had no other centralized way to organize such funding projects). Reagan's Star Wars program for the militarization of space, for instance, was focused on research in part meant to spin off a dazzling array of future civilian products and projects.

By 1991, the interweaving of the Pentagon, vast weapons corporations, the military-funded academy, the intelligence agencies, lobbyists, and politicians who relied on all of the above had become so much the life of Washington and the nation that, when the Soviet empire collapsed in a remarkably peaceful fashion, there was no real hope that anyone in Washington would stop for a second to reconsider our way of war, much less offer the American public or the world a "peace dividend" of any sort. There is no greater evidence of how deeply our society had been Pentagonized than the continuing commitment to war and a vast nuclear arsenal in a world that briefly threatened (and that's the only word for it in this context) to lack all significant enemies.

What was striking though into the 1990s was how much of this had taken place out of sight of the ordinary citizen. It's what gave American militarism its distinctive form. In all those years when the Pentagon was creating militarized little Americas all over the globe, the creeping militarization of our own society was taking place largely beyond view and with none of the classic trappings that proud and assertive militaries like to display. There were in most of those years, no troops in the streets, no major parades, few uniforms in the news (when a war wasn't being reported), and so on.

A tipping point, however, seemed to arrive in the younger Bush years under the rubric of the war on terror. The police have since been given a military once-over and it has become increasingly commonplace in cities like New York and at airports, train stations, or even in subways, to see well-armed troops in uniform on patrol or at rest. (During the Democratic convention in Boston, for instance, I leapt into a taxi to rush from one site to another and, as we passed police squads on horses, groups of troops in camo with impressive guns slung over shoulders, and omnipresent helicopters hovering overhead, the driver, an immigrant from Africa, suddenly said to me, "This is the first time since I got here that I've felt like I was back home…"

How true. Boston suddenly had the look of some Third World dictatorship. This visual change has gone hand in hand with other changes -- the final defanging of Congress as an agency of budgetary oversight, the breaking down of barriers between spying abroad and at home as well as between military and civilian policing duties, the further bloating of the military budget, even the "privatization" of many military functions fusing the military and the corporate in yet another way -- which I briefly reviewed in our previous exchange of letters and which leave the Pentagon as the 800-pound gorilla in just about any room.

Where once the world out there was divided into military "commands," with the setting up of a North American Command (NORTHCOM), we too are now included. Meanwhile, the Pentagon takes ever more gargantuan bites of our budget even though, other than small groups of fanatic opponents, we have no conceivable enemies capable of seriously threatening us; and both presidential candidates have no choice but to promise the military yet more money, more troops, more weapons, more of just about everything.

Here's a small sign of the times: In previous decades, as Pentagon budgets grew and its weaponry became ever more expensive and exotic, Congress, that constitutionally-mandated holder of the power of the purse, still attempted to exert some small oversight on at least the Pentagon's more egregious workings. This usually expressed itself in criticism of Pentagon pork (overpriced simple objects purchased by underwhelmed military officials) and useless weapons programs like the B-2 bomber that were repeatedly challenged in Congress but, like so many Draculas with a host of vampiric followers in innumerable congressional districts, simply refused to die. Such modest attempts to rein in the military were reflected in our press in periodic rounds of outraged articles about ridiculous weapons systems and ludicrous Pentagon purchases. These have, strikingly, largely disappeared from the media. I never thought I'd be nostalgic for those peripheral pieces of reportage about million-dollar monkey wrenches or toilet seats.

So, on the one hand you, Jonathan, argue that we have an unexpectedly constrained imperial world out there; on the other hand, constraints here in the "homeland" seem to be evaporating. What's left is a vast, sprawling, interlocking set of institutions, anchored in the uniform, intent on creating weapons of an ever more horrific sort to be tested in small wars elsewhere, and on garrisoning the globe. The growth of this strange, still only half-seen creature seems at the moment unstoppable. Like a cowbird baby in some smaller bird's nest, it has long outgrown the rest of the crowd and yet is still insistently demanding more food. Add into this mix in a not-so-distant post-Iraq world in which the finest military on the planet has suffered an incomprehensible defeat at the hands of groups of ragtag nobodies, an angry (not to speak of confused) officer corps; throw in the odd charge of betrayal (who lost Iraq?), sure to happen should there be a Kerry presidency, and you have a combustible mix here in these United States.

While the heft of the unelected Pentagon has grown beyond all bounds and probably for the foreseeable future (short of a staggering, unexpected upheaval) beyond all restraining control, there is another no less unbalancing phenomenon at work. Our democratic system seems to be rapidly growing ever feebler, ever more constrained, as the present billion-dollar presidential election is making all too clear. In fact, if you think for a moment about our most recent candidates for president, amid a nation of several hundred million souls, doesn't it tell you something that all of the last four elections and this year's as well will have been won by a candidate who attended Yale University. In two of them (1992 and 2004), both candidates attended Yale. Yalies include the Elder and Younger Bushes, Bill Clinton (Georgetown and then Yale law school), and John Kerry. Add in two losing candidates from Harvard, Al Gore and Michael Dukakis (Swarthmore and Harvard Law School), and the only odd duck in the group is Bob Dole who attended Washburn Municipal University in Kansas.

Narrowing it down further, the present election is being fought out not just by two very wealthy Yalies, but by two men who belonged to the same tiny, ultra-hush-hush secret society, Skull and Bones, while at Yale. Now, I'm not especially conspiracy-minded -- or rather, while I believe that our world may be riddled by conspiracies, I'm not much for conspiracy theorists who, I suspect, are the last to know -- but such an "only in America" candidate-selection system certainly implies a kind of bankruptcy from a democratic point of view.

The fragility of our republic can be felt no less in the anxious discussions of touch-screen voting fraud and election theft that have migrated from the Internet to the op-ed pages of our major papers. Here are words that once would have been used in describing some Third World country, but now are increasingly attached to discussions of ours: stolen election, coup d'état, cabal, dynasty. Wouldn't it be a painful irony if, at the very moment when we were proven to be a failed military empire, in the "homeland" it was the republican parts of our system that were "paralyzed." What happens then, when the empire -- or simply the angry centurions -- return to NORTHCOM?

Tom Engelhardt, who runs the Nation Institute's Tomdispatch.com ("a regular antidote to the mainstream media"), is a co-founder of the The American Empire Project and consulting editor at Metropolitan Books. He is the author of The End of Victory Culture among other books.